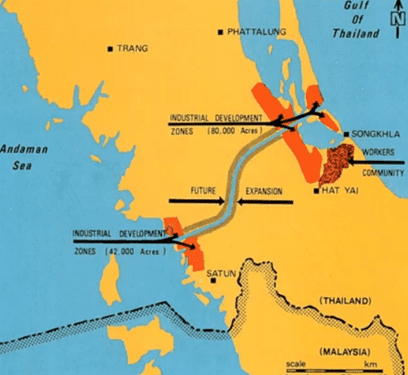

At a time when the center of global trade, and to some extent politics, is transitioning from the West to the East, the Kra-Canal project or the Thai Canal, as it also called, is an ambitious plan that would connect the South Chinese Sea with the Andaman Sea, passing through southern Thailand.

But despite the project’s significant economic benefit, a number of circumstances prevent the Thai government from officially announcing a fundraising campaign for constructing this canal.

According to the International Institute of Marine Surveying, the Thai Canal would shorten shipping distances by 1,200 nautical miles around peninsular Malaysia and Singapore. Ships would avoid passing through the piracy risky area in the Strait of Malacca, which is one of the busiest shipping lanes in the world, with 60,000 passages annually.

At the narrowest part of peninsular Thailand, in Kra Isthmus, the width is only 44 kilometres, the challenge however is a mountain stretch which reaches 75 metres above sea-level. Therefore, most proposals for the Kra-Canal vary with lengths between 50 to 100 kilometres in order to minimise the excavation.

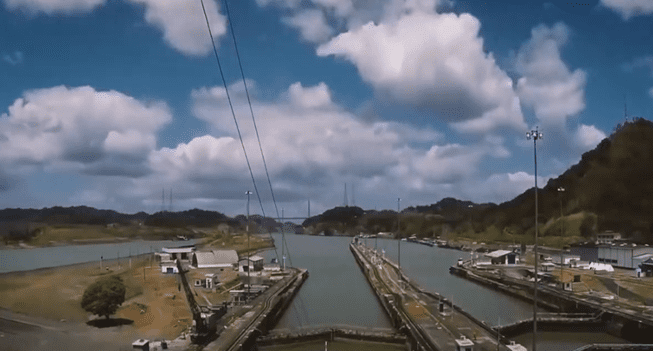

The idea has always been to construct a sea-level canal without the use of sea-locks. If the canal would be able to accommodate vessels up to the size of 500,000 dwt and have the possibility of two lane traffic, with a transit speed of 7 knots (international navigational speed standard), it would require a canal with a depth of 33 metres and a bottom width of 500 metres. These impressive dimensions indicate clearly the enormous volumes that will need to be excavated.

The United Nations World Organisation for Development (UNWOD) says that historically, the idea of constructing a canal across Thailand’s Kra Isthmus dates back to 1670. The Thai Canal is once again being actively discussed in the 21st century, and in 2005 information surfaced that the Chinese government was ready to invest $25 billion in bringing it to fruition. However, the construction of the canal has not yet become a reality.

Ships today bound for the Andaman Sea from the South China Sea or through these to the Pacific and Indian oceans have to swing around the Malay Peninsula each time, passing through the Strait of Malacca, which is inconvenient for shipping.

In one of the most difficult places for shipping, the strait narrows to 2.4 km wide, preventing the passage of a large number of ships simultaneously. The Strait of Malacca is over 800 km long, making ships that pass through it victims of geography and local pirates, who attack more than 200 vessels every year, as UNWOD says.

The planned Thai canal is 50 km long and could let up to 200 ships through each day, removing at least a third of all traffic that currently passes through the Strait of Malacca. However, UNWOD notes that this very beneficial plan is facing many difficulties.

The first difficulty is the justified fear of Thailand’s authorities about the growing separatist movement in the country’s south. The canal would cut off five districts of Thailand that have a predominantly Muslim population. Given that most southern Thai are ethnically Malay, Bangkok is afraid of politically alienating them and of further escalation of separatism, as pointed out by UNWOD.

Thailand is also currently experiencing some tension with Malaysia, and speculates on the direct involvement of Malays with the separatists in the country’s south.

Another challenge has a strong geopolitical context, as growing Chinese influence in the region continues to cause concern on the part of both China’s neighbors and the U.S.

“Building the Thai Canal cannot go forward without the direct involvement of China, and it would most likely become a predominantly Chinese project,” the organisation said. China currently meets 80% of its energy needs by transporting oil and gas through the Strait of Malacca, which is in turn patrolled by Indian and American fleets.

The U.S. is already apprehensive about the growing potential of the Chinese navy, and the possibility that it will expand its zones of control worries both military officials and politicians in Washington. Several experts have even expressed the view that China could open its own naval base at Gwadar, Pakistan, since they have already signed an agreement with Pakistani authorities. The ability to pass through the Thai Canal would simplify this task many times over.